Gregory Thaler is Associate Professor of Environmental Geography and Latin American Studies at Oxford University . He tells Srijana Mitra Das at TE about ways to ensure healthier oil:

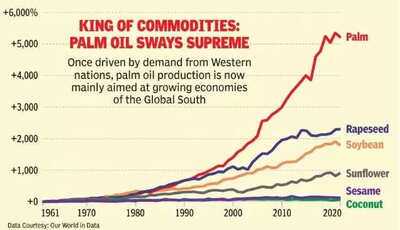

The pace of deforestation on Earth is breath-taking. The loss of forests itself is intertwined with the rise of humanity — in just the last three centuries, Earth has forsaken 1.5 billion hectares. Palm oil plays a huge role in this. Between 2001 to 2015, studies find its plantations expanded over 22.4 million hectares — a rise estimatedly of 167%.

While the statistics are shocking, Gregory Thaler remains calm, discussing palm oil’s worldwide web. Outlining his research, he explains, ‘I work broadly on how power influences social and ecological change. I do this with two major research programs. One looks at the political ecology of tropical forest landscapes and how different actors, policies and power relations affect de-forestation, agriculture and livelihoods in Indonesia, Brazil and Bolivia. The second looks at global environmental governance and how different institutions structure environmental decisions — in this, I also study environmental NGOs.’ Discussing palm oil, Thaler says, ‘Its spread is extraordinary as is the role it plays in modern society. This oil is primarily produced from the West African palm — traditionally, this was done by small farmers in community operations. Over the last two centuries, it became a major industrial crop, grown in vast plantations, processed in massive factories. It is pervasive in multiple consumer goods, one of the most common inputs in detergent, cosmetics, adhesives, wet wipes and processed foods, from biscuits to chips, noodles to ice-cream.’

Palm oil has a particular tenacity — it makes wafers crisper and keeps ice-cream from melting. Its impacts on the planet and people are somewhat different though. Thaler explains, ‘Its widespread industrial expansion has tremendous consequences for both ecologies and live-lihoods. In Indonesia, palm oil plant-ations have caused massive deforestation — that comes with huge ecological effects in terms of losses of biodiversity and climate change as you replace carbon-dense natural forests with a single-crop plantation. Further, people in these regions lose their land, get pulled into exploitative labour regimes and exposed to toxic chemicals.’ The health impacts don’t stop there. Thaler says, ‘This proliferation of junk food that oil palm is part of is affecting people’s diets globally now — the worldwide obesity epidemic is driven in part by this expansion of cheap industrially produced oil inputs.’ Yet, Thaler is sceptical of technological solutions which claim to address at least palm oil’s ecological impacts, promising more oil from less land.

As he says, ‘There are problems with those narratives, the first being basic political economy — these innovations are deployed in an industrial capitalist system. So, these basically facilitate greater production and uptake globally — the driving incentive remains profit. Hence, there is no level of sufficiency at which industrial actors will stop producing and using more palm oil.’ There is also some greenwashing involved. Thaler explains, ‘These ‘green’ supply chains often depend on destructive nongreen ones — you separate zones of supposedly sustainable production but, in fact, their green palm oil is coming from one cleansource while overall expansion is still fulfilled through new deforestation, plantations and dirty palm oil.’ Thaler pauses and then emphasises, ‘I am also sceptical of these narratives because I think we should consider what goals we are working towards — a world wherefood oil, a fund-amental staple, is produced thousands of miles away and managed by a few multi-national corporations is not a recipe for environmental sustainability or socioeconomic development. We should question the industrial corporate system being the best way to satisfy people’s fundamental food needs.’ Yet, this system drives ‘the 21 st century land rush’. Thaler explains, ‘Following the financial and food crises of 2007-08, there was an increase in international land deals, arranged by different actors — some were government-linked entities, trying to secure food production for their citizens, as certain Persian Gulf states did. There was also a broader involvement in land by corporate actors and investors like pension funds.

International land investment in the global economy is not new — but after 2008, we saw a dramatic increase. The fundamental idea was land as a key asset, especially in times of economic and climate volatility — hence, we continue to see states and global investors, seeking ways to control land and secure their supply chains. We also see conflicts over land between such interests and local communities.’ Palm oil — the ubiquitous grease around this vast global industrial machine — is part of our modern epic. Can it be made more just? Thaler says, ‘Yes, solutions include production and consumption. For the first, oil palm can be profitably and effectively produced by small farmers who use more biodiverse systems. It’s not necessary to only grow it in huge corporate plantations. It’s also important to shorten our supply chains — it will never be ecologically or socially desirable to keep shipping huge volumes of staples around the world. We should localise such production far more. Traditionally, people used a variety of crops to meet their needs — it’s not necessary to use palm oil everywhere. We should explore alternatives which work better, according to local ecologies and farming systems. Re-localising and supporting smaller-scale production will lighten the world.’ And many of its citizens, currently burdened under palm oil-based foods which are anything but nourishing.

The pace of deforestation on Earth is breath-taking. The loss of forests itself is intertwined with the rise of humanity — in just the last three centuries, Earth has forsaken 1.5 billion hectares. Palm oil plays a huge role in this. Between 2001 to 2015, studies find its plantations expanded over 22.4 million hectares — a rise estimatedly of 167%.

While the statistics are shocking, Gregory Thaler remains calm, discussing palm oil’s worldwide web. Outlining his research, he explains, ‘I work broadly on how power influences social and ecological change. I do this with two major research programs. One looks at the political ecology of tropical forest landscapes and how different actors, policies and power relations affect de-forestation, agriculture and livelihoods in Indonesia, Brazil and Bolivia. The second looks at global environmental governance and how different institutions structure environmental decisions — in this, I also study environmental NGOs.’ Discussing palm oil, Thaler says, ‘Its spread is extraordinary as is the role it plays in modern society. This oil is primarily produced from the West African palm — traditionally, this was done by small farmers in community operations. Over the last two centuries, it became a major industrial crop, grown in vast plantations, processed in massive factories. It is pervasive in multiple consumer goods, one of the most common inputs in detergent, cosmetics, adhesives, wet wipes and processed foods, from biscuits to chips, noodles to ice-cream.’

Palm oil has a particular tenacity — it makes wafers crisper and keeps ice-cream from melting. Its impacts on the planet and people are somewhat different though. Thaler explains, ‘Its widespread industrial expansion has tremendous consequences for both ecologies and live-lihoods. In Indonesia, palm oil plant-ations have caused massive deforestation — that comes with huge ecological effects in terms of losses of biodiversity and climate change as you replace carbon-dense natural forests with a single-crop plantation. Further, people in these regions lose their land, get pulled into exploitative labour regimes and exposed to toxic chemicals.’ The health impacts don’t stop there. Thaler says, ‘This proliferation of junk food that oil palm is part of is affecting people’s diets globally now — the worldwide obesity epidemic is driven in part by this expansion of cheap industrially produced oil inputs.’ Yet, Thaler is sceptical of technological solutions which claim to address at least palm oil’s ecological impacts, promising more oil from less land.

As he says, ‘There are problems with those narratives, the first being basic political economy — these innovations are deployed in an industrial capitalist system. So, these basically facilitate greater production and uptake globally — the driving incentive remains profit. Hence, there is no level of sufficiency at which industrial actors will stop producing and using more palm oil.’ There is also some greenwashing involved. Thaler explains, ‘These ‘green’ supply chains often depend on destructive nongreen ones — you separate zones of supposedly sustainable production but, in fact, their green palm oil is coming from one cleansource while overall expansion is still fulfilled through new deforestation, plantations and dirty palm oil.’ Thaler pauses and then emphasises, ‘I am also sceptical of these narratives because I think we should consider what goals we are working towards — a world wherefood oil, a fund-amental staple, is produced thousands of miles away and managed by a few multi-national corporations is not a recipe for environmental sustainability or socioeconomic development. We should question the industrial corporate system being the best way to satisfy people’s fundamental food needs.’ Yet, this system drives ‘the 21 st century land rush’. Thaler explains, ‘Following the financial and food crises of 2007-08, there was an increase in international land deals, arranged by different actors — some were government-linked entities, trying to secure food production for their citizens, as certain Persian Gulf states did. There was also a broader involvement in land by corporate actors and investors like pension funds.

International land investment in the global economy is not new — but after 2008, we saw a dramatic increase. The fundamental idea was land as a key asset, especially in times of economic and climate volatility — hence, we continue to see states and global investors, seeking ways to control land and secure their supply chains. We also see conflicts over land between such interests and local communities.’ Palm oil — the ubiquitous grease around this vast global industrial machine — is part of our modern epic. Can it be made more just? Thaler says, ‘Yes, solutions include production and consumption. For the first, oil palm can be profitably and effectively produced by small farmers who use more biodiverse systems. It’s not necessary to only grow it in huge corporate plantations. It’s also important to shorten our supply chains — it will never be ecologically or socially desirable to keep shipping huge volumes of staples around the world. We should localise such production far more. Traditionally, people used a variety of crops to meet their needs — it’s not necessary to use palm oil everywhere. We should explore alternatives which work better, according to local ecologies and farming systems. Re-localising and supporting smaller-scale production will lighten the world.’ And many of its citizens, currently burdened under palm oil-based foods which are anything but nourishing.

You may also like

Rs 2,500 to eat in a stranger's apartment? With no big investment, hosts are earning lakhs with new dining trend

Molly-Mae Hague inspired by Paris Fury over latest move as she rekindles romance

'I found little-known UK spot where you can get huge ice cream for bargain price'

Man buys pet cats but has specific rule when it comes to naming them

Netflix's gripping new NHS documentary release date and where to watch